Maclean’s: For decades, relatives of victims and survivors of Iran’s bloody decade felt silenced and forgotten, cut off from any means of seeking justice. The International Criminal Court cannot prosecute crimes committed before July 1, 2002; and even if it could, Iran does not accept the court’s jurisdiction.

Maclean’s: For decades, relatives of victims and survivors of Iran’s bloody decade felt silenced and forgotten, cut off from any means of seeking justice. The International Criminal Court cannot prosecute crimes committed before July 1, 2002; and even if it could, Iran does not accept the court’s jurisdiction.

But the quasi-judicial process has no legal standing

Maclean’s – Canada

by Michael Petrou

Nina Toobaei last saw her younger brother, Siamak, in an Iranian prison in 1987. She kissed her hand and placed it against the glass dividing them. He did the same. Then she left Iran for a new life as a refugee in Canada.

Nina Toobaei last saw her younger brother, Siamak, in an Iranian prison in 1987. She kissed her hand and placed it against the glass dividing them. He did the same. Then she left Iran for a new life as a refugee in Canada.

Two years later, Siamak was given a day pass to visit family. On a trip to the market, he slipped away. Toobaei and her mother and father allowed themselves to believe he had escaped for good, and that one day they would hear his voice on the phone, or he would show up in person.

“Our eyes were on the door for 18 years,” she says. Her brother never came.

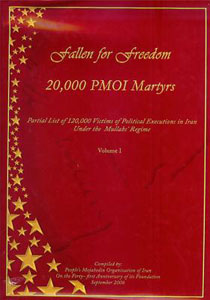

It wasn’t until one of Siamak’s friends and fellow prisoners wrote a memoir in exile that his family learned he had been recaptured and executed—one of perhaps 20,000 political prisoners killed by the Islamic Republic during the 1980s. Many, such as Toobaei’s uncle Bahman Nayeri, were leftists; others, including Siamak and another uncle, Bijan Nayeri, belonged to the People’s Mujahedeen of Iran, whose members actively fought the Iranian regime, including with bombings and assassinations.

No one has ever been held to account for the mass murder of prisoners during the 10 years that followed the Islamic revolution. Some of the perpetrators now occupy leading positions within the Islamic Republic—while the mothers of executed prisoners are harassed and abused when they mourn their children at an unmarked mass grave in Tehran’s Khavaran cemetery, where many of them are buried.

Toobaei and her mother and father are denied even this meagre comfort. They don’t know where Siamak’s body is.

“Once, my mom told me that she wishes he was also in Khavaran, so that she could go sometimes and be where his bones are,” Toobaei says, her voice breaking.

“When you have a grave, sometimes you go there and you talk to him. When you don’t, it hurts.”

For decades, relatives of victims and survivors of Iran’s bloody decade felt silenced and forgotten, cut off from any means of seeking justice. The International Criminal Court cannot prosecute crimes committed before July 1, 2002; and even if it could, Iran does not accept the court’s jurisdiction.

The United Nations might establish a tribunal, as it did for crimes committed in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, but Iran has powerful friends on the Security Council and this is unlikely. And the West has always been more concerned with Iranian terrorism and its nuclear program than the savagery the state visits on its citizens.

This led survivors of the massacres to create their own forum for justice. The Iran tribunal, established in 2007, has no legal standing. Its creators, however, modelled it on other international legal tribunals. Steering committee members Sir Geoffrey Nice, a British barrister, and Payam Akhavan, a professor of international law at McGill University, both worked on the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Akhavan also advised the prosecutor’s office at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

“We took great care to have a credible process, which would be perceived by the Iranian public and the wider international community as at least a quasi-judicial process. And that meant that it not be seen as a politicized process, but as a historical record and a judgment based on international law,” says Akhavan.

“At least half of justice, if not the greater half, in the context of crimes against humanity, is to expose the public to historical truth. It’s not just about arresting someone and putting them in prison, as important as that may be.”

The tribunal, which was funded through donations and is independent of any government, heard from almost 100 witnesses who testified in two phases this year. In June, a truth commission took place in London. The primary purpose of this stage was to allow victims to tell their stories in a formal setting.

“The Iranian government has committed two crimes against these people,” says Kaveh Shahrooz, a Toronto lawyer and a prosecutor on the tribunal. “One is to imprison, torture, or kill their loved ones. And the second crime is to deny what happened to them and to prevent them from speaking about it.”

The second phase took place in The Hague in October. This phase more closely mirrored a formal legal tribunal. The prosecution argued that the Iranian regime is guilty of crimes against humanity. Iran was asked to take part, but did not acknowledge or respond to the invitation.

In an interim judgment, issued in late October, the tribunal’s judges wrote: “The evidence speaks for itself. It constitutes overwhelming proof that systemic, systematic and widespread abuses of human rights were committed by and on behalf of the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

“There are six forms of gross human rights abuses to which the evidence presented to the Truth Commission and this tribunal point incontrovertibly: murder; torture; unjust imprisonment; sexual violence; persecution and enforced disappearance.”

The judges recommended that the United Nations establish a commission of inquiry to investigate these atrocities. Regardless of whether this occurs, those involved in the tribunal say it has already been a success. Its proceedings were filmed and broadcast on Persian satellite channels that are surreptitiously watched inside Iran.

McGill’s Akhavan believes the regime itself has been forced to respond. A recent news story on the Baztab news site, thought to have ties to conservative politicians in Iran, claimed that Iran’s current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, intervened to spare leftist political prisoners from likely execution in 1988, when thousands of leftists and People’s Mujahedeen were killed in a particularly bloody massacre.

The story isn’t credible, says Akhavan, but he argues it would not have been published unless those close to Khamenei wanted to shield him from public anger. “This is a turning point in the culture of accountability in Iran,” he says. “The most untouchable leaders are realizing that they’re answerable to the people, that people will not forget.”

Survivors have never forgotten. One victim, who now lives in Canada and asked not to be named, spent eight years in prison. A leftist, he was arrested for possessing posters and distributing leaflets. Hundreds of prisoners were executed one week during his incarceration. The killing began at dinnertime. He and the other inmates were forced to listen to the gunfire just beyond one of the walls enclosing them. Nobody could eat. They just counted the shots.

“This is not for revenge at all,” he says, explaining why he testified. “I don’t believe in the death penalty. We have to stop this circle of bloodshed in Iran.”

Instead, he says he wanted to help document what happened. “I have to testify because of the people in those mass graves. I know many of them. This shouldn’t happen in the future. That was the reason—so it wouldn’t happen to our people again.”

Nina Toobaei says testifying helped her begin to heal. When she returned to Canada, some of her family members had changed, too. “My mom was happy. Her voice was more alive. You’re doing something. You’re taking one step, and that makes you happy. Because we could raise our voice.”

Maclean’s is Canada’s only national weekly current affairs magazine.